At least ten acronyms exist to indicate that an email’s message is contained solely within the subject line:

| EOM (or EOL) | End of message (or End of line, for Tron fans) |

| n/m | No message |

| n/b | No body |

| NT | No text |

| SO: | Subject only |

| 1L | One liner |

| NNTO | No need to open |

| SIM | Subject is message |

| SSIA | Subject says it all |

To some, these are big-brain brevity. To others, pointless patois. And that’s sort of the point! Subject lines can be whatever you want them to be.

It’s a wonder that email has had, almost since the beginning, a field to contain these multitudes, an unstructured header that we can use to filter, forward, label, and archive emails with a simple automation or a quick glance. Because, to the people who designed email, the plaintext subject line was far from the only option for describing an email’s contents.

Your inbox as a text file

Messaging across a computer network existed in a few different forms before Steve Crocker and others at ARPANET began standardizing it. Tom Van Vleck, for example, explained in a 2001 article about MIT’s Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) that asynchronous communication was one of the first things remote file servers were used for in the 60s. “When CTSS users wanted to pass messages to each other, they sometimes created files with names like "TO TOM" and put them in "common file" directories.” The first digital subject lines were filenames.

ARPANET took a slightly different approach, creating a text file that acted as your entire inbox and letting others add to that file via the File Transfer Protocol. “A mail box, as we see it, is simply a write only (from the Network) sequential file to which messages and documents are appended,” Richard Watson wrote in RFC221, just before planting the seed for subject lines further down, “At the head of the message or document sent to mail box number 0 there is to be an initial address string terminated by a form feed…Comments could also be included in the address string.” It would be years before message headers got any traction, though.

Even though three-quarters of all ARPANET traffic was email in the early 70s, it was still a matter of opening your “inbox” and viewing everything people had sent you as a unified text file. There were no breaks between the messages and no way to reply to individual messages directly. The proposed solutions to these issues were legion.

RFCs represented distributed brainstorming sessions. Steve Crocker lamented the perceived authority of written communication and would rather members of the group share a bad idea than keep a good one to themselves. “The ARPANET's earliest users were constantly generating a steady stream of new ideas, tinkering with old ones, pushing, pulling or prodding their network to do this or that, spawning an atmosphere of creative chaos,” Katie Hafner wrote in Where Wizards Stay Up Late. And the email subject line weathered it all.

Titles, keywords, remarks, and reasons

Starting in March of 1973, Abhay Bhushan, the original author of the File Transfer Protocol, led the charge to add new email-specific commands to FTP. He wanted to add an Author field below the From field, because assistants often sent messages written by their bosses, as well as a Type field to categorize Urgent, Ordinary, and Long messages.

Then, in RFC469 (a summary of Bhushan’s recommendations) there was a description of his suggested Title command, which included the first reference that I can find to what we all call it today: “The "title" (i.e. subject) of the mail is to be terminated by period carriage return.”

From that point forward, subject lines took on a role that has remained mostly unchanged to this day, being “especially useful for recorded mail, since indexes on key words in the title can be produced relatively easily, and facilitate searching for mail. For this reason, the title should be a succinct indicator of the contents.” This, more than 10 years before the USPS tried to co-opt email and 20 years before email worked with non-English languages!

Most of Bhushan’s proposed commands, including Title, were tossed into a 40-page, 10k-word Mail Protocol proposal that also included a laundry list of backend specifications. Knowing it wouldn’t get approval any time soon, he split off the conversation about standardized headers, focusing on three: From, Date, and Subject.

Other people, however, wanted more headers. A lot more. RFC680 once again broached the idea of a distinction between who wanted the message sent, this time as From, and the person who actually sent the message, in a separate Sender header–a distinction that continues to this day despite being mostly unused. There were also fields for Keywords, Precedence, and Special-Handling, along with Message-Class to describe “the ‘legal’ status of the message. Examples: Official, Unofficial, Record, Off the Record, Junk Mail.” These are all superfluous in the face of an open-ended subject line!

It didn’t stop there. RFC724 suggested that “Parenthetical remarks, or comments, can be included and syntactically recognized as such within some header items.” To wit the author included Wilt (the Stilt) Chamberlain at NBA as an example of how parantheticals might be useful in the From field, for those MSN Messenger vibes. In a later revision, all bets were off and senders could create their own header fields for private or public use.

While user-defined headers ended up being useful for things like X-Mailer, which identifies the sending software, and the self-explanatory X-Spam-Score, there were growing pains. Katie Hafner included one example in her book **of a user sarcastically sending an email in 1977 that included more than two dozen unnecessary headers, including:

- Reason: Did Godzilla need a reason?

- Spelling-errors-this-message: 0

- Weather: Light rain, fog

- Psych-evaluation-of-sender: Slightly unstable

- #-people-in-terminal-room: 12

The reason it’s so hard to imagine receiving an email with that many unnecessary headers today wasn't the actions of a standards committee or a technical limitation. It was, instead, that email went mainstream. Through the 80s and early 90s, the average user shifted from government workers and academics to corporate employees and hobbyists. And, as early as 1986, studies had found that office workers were already fatigued by email, overestimating the number of messages they sent and received. So, software adapted accordingly.

Software-defined subject lines

Early email clients like Eudora, a favorite among power users, truncated subject lines at around 50 characters. Message headers were hidden until you clicked the BLAH, BLAH, BLAH button. The first webmail platforms, like Hotmail and RocketMail, went even further with interfaces stripped to just four columns: From, Date, Subject, and Size.

Image via /r/nostalgia

And so, with all of the redundant headers deprecated or hidden away, the subject line faced yet another crisis: spam. As the most visible part of any email, and thus the most likely to deceive recipients, subject lines were where most, sometimes all, spam filtering took place.

Filter.px, the precursor to SpamAssassin, caught 90% of spam mostly by “[checking] the subject line and message-id of an inbound mail against the database, seeing if anyone else's filter already tagged it as spam beforehand. It updates this table if it tags the email as spam as well.” A start for sure, but easy to sidestep.

Paul Graham’s now-infamous A Plan For Spam in 2002 provided a far superior approach with Bayesian filtering, specifically, including different weights for flagged words in headers versus the body. “For example, in the current filter, free in the Subject line has a spam probability of 98%, whereas the same token in the body has a spam probability of only 65%.” People saw less unsolicited crap in their inboxes and fewer unhinged subject lines…until October 2010.

Words are sufficient

“114 characters in the core emoji set are mapped to sequences of one or more characters available in Unicode before Version 6.0,” read the Unicode Consortium’s FAQ page on Emojis, published the day they were added to the standard. And, because MIME added support for Unicode in email headers 12 years earlier in RFC2279, they were grandfathered in.

“Emoji spam (specially rocket) is the litmus test for “people i dont want to work with” @throwmeout123 commented on a Hacker News post about emojis. “Any email with an emoji in the subject line is an email I'm not going to read,” @wlesieutre replied. Most people who hate emojis in subject lines don’t hate the characters themselves, and they likely don’t care about professionalism or the lack thereof. They just want their inbox to be a place of valuable information and communication.

“The title should be a succinct indicator of the contents,” Michael Kudlick wrote in RFC469. That, when combined with a recognizable and trustworthy address in the From header, doesn’t need emojis to stand out or be valuable.

We didn’t need a Keyword header, or ones for Precedence, Special-Handling, and Message-Class. We didn’t even need to change how subject lines work to stomp out spam.

A plaintext subject line is enough for most emails [EOM].

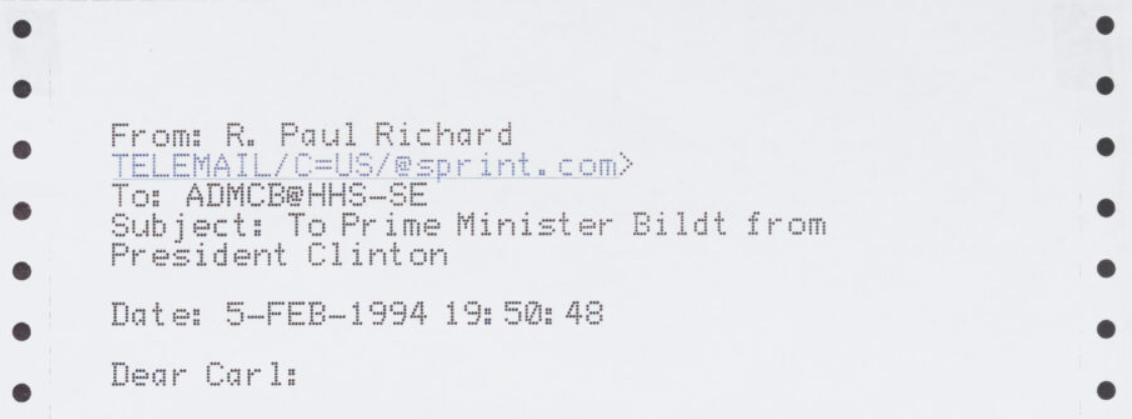

Header image from National Museum of American Diplomacy.