Nearly 12 years after its end of life and 30 after its v1.0, fans of arguably the trendiest desktop email clients of all time came out of the woodwork, shouting Eudora’s praises.

“Probably one of the few people left who still use it on a daily basis,” a Slashdot user wrote in response to the Computer History Museum releasing the email client’s source code. That hunch turned out to be pretty far afield.

“Eudora is a major reason my home desktop is still on OS X 10.6,” someone admitted in a Hacker News comment. “Eudora is on my machine to stay for the time being. It'll be there until the POP/IMAP protocol ceases to work!” another person proclaimed.

Then, there was the board chairman for the Computer History Museum himself. In the article announcing Eudora’s open-source status, Len Shustek insisted it was “the finest email client ever written, and it has yet to be surpassed. I still use it today.”

But if it was so great, why is Eudora buried in the archives instead of headlining a Wirecutter recommendation? There are many reasons. And somewhere further down that list is the one I find most interesting.

Eudora was, from the very beginning, quirky software built for power users. Like a film director who respects their audience, skipping over exposition and letting them fill in the blanks. It’s not an approach that works for every app or newsletter or whatever else you’re creating. But when it works, people fight to keep your work alive.

First users in, last users out

A little more than a year after Steve Dorner began work on Eudora, writing an average of 4,000 lines of code per month, the University of Illinois released the email client for free in 1988.

A few years later, Richard Stallman would publish the first General Public License and, paradoxically, Universities would shift from releasing their software in the public domain to thinking of it as a commercial asset. It was around that time when Qualcomm asked to buy (license, technically) Eudora and hire Dorner to continue developing it, a deal the University of Illinois was happy to take.

The first order of business after the change in management was to port the Mac-only version over to Windows for internal use among Qualcomm employees. They loved it. Project manager John Noerenberg recalls hearing "One financial executive at Qualcomm saying, 'I used to hate email. But I love Eudora!’”

Screenshot via University of Padua

A big part of what made Eudora so enjoyable to use was that it was one of the earliest email clients with a graphical user interface. That made it a breeze to experiment with and customize its unusually large featureset. You could, as early as version 1.4, schedule messages to send at specific times, edit your Quick Recipient list in the File menu, and switch between quoted-printable and base64 encoding to send messages with special characters at a time when English was the lingua franca of email.

Eudora became very popular very quickly. The team managing it grew alongside and invited users to send postcards about what they liked most in the software. Thousands of missives streamed in, disproportionately from people who lived and breathed email every day! It was participation bias and user-driven development at its best.

Software with personality

Qualcomm held off on monetizing Dorner’s software for a few years. But with 50 full-time employees working on it, that didn’t make sense for long. They rejigged Eudora into three tiers: Light (free), Sponsored (ad-supported) and Pro (paid). Even with the lowest tier, however, Eudora gave users far more flexibility and power than most other options of the time.

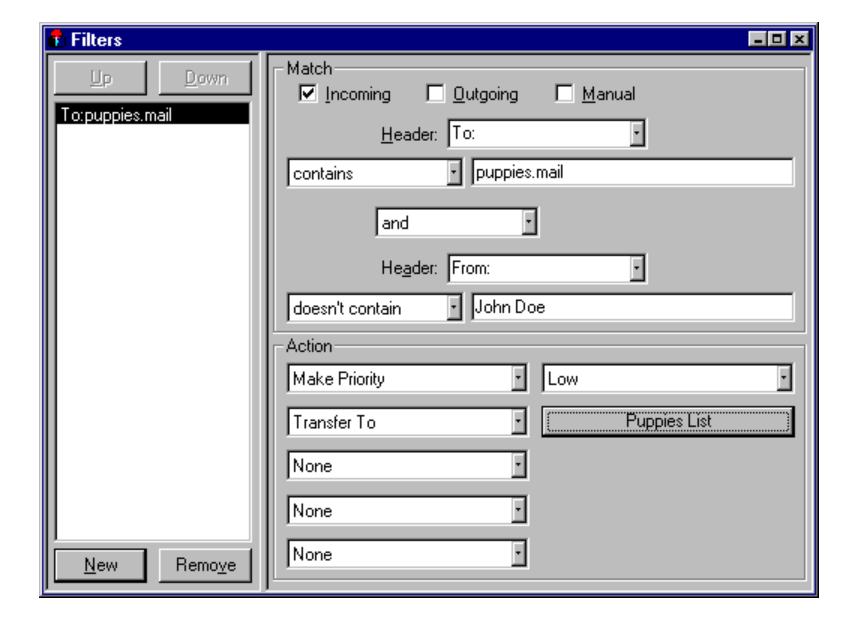

Screenshot via Bertola.eu

Eudora Light 3.0 for Windows (which, fun fact, was coded in a completely different language, by a completely different team, than the Mac version) allowed multi-criteria custom filters, the ability to create emails from inside other software, and enough keyboard shortcuts to make power users weep.

Later Mac versions included URI settings. You could copy a bit of code into a new message, and the string would automatically become a link. When clicked, URIs would let you change impossibly granular settings that weren’t listed anywhere in the software or its documentation.

There was x-eudora-setting:32698, for instance, which let you set the maximum number of pixels in an image attachment for it to be downloaded automatically. Or setting 32662, to change the width of the function key labels in the toolbar. Or 7008, to edit the tooltip of the queue button. This sort of flexibility attracts the attention of particularly vocal users.

“[Eudora] has an incredible feature that every single mail client should have. Any feature in the menu list, any action there, can be added as a button,” Steve Wozniak gushed in a Lifehacker interview. “You can script actions to the buttons, too, so I can quickly copy messages to my assistants. There are scripts I wrote for joke lists so I can forward a message, remove the brackets and formatting, and make sure all the original attachments are included, to a pre-defined ‘joke’ group. Apple's Mail app just isn't scriptable enough to really handle my mail buttons.”

And the vibes. Eudora’s earliest notification pop-ups included a rooster with a letter in its beak when you had new mail and a snake when you didn’t. Because "The idea was that the rooster would have brought your mail, but the snake ate it first," Dorner told the New York Times.

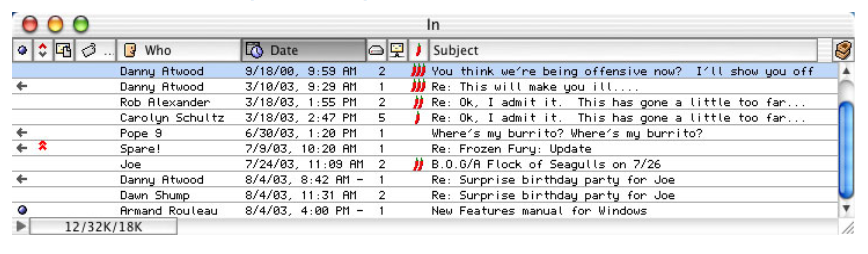

Screenshot via Stanford University Helpdesk

Later, there would be a button for furling and unfurling message headers with BLAH, BLAH, BLAH written on it. Version 6 introduced MoodWatch, which labeled incoming and outgoing messages with chili peppers and ice cubes, depending on the presence of possibly offensive language. People loved it!

At its peak, Eudora served 18 million users and maintained a 63.5% worldwide market share among email clients. Unfortunately, the best-laid plans of devs and dotcoms often go awry.

An onslaught of spam meant that email started to become more chore than delight. Users flocked to dumbed-down mailboxes and then-nascent social media. Those whose work took place in an inbox were having Outlook foisted on them.

Qualcomm saw declining numbers and hit the eject button in 2006, discontinuing development. They wanted Eudora to be a blockbuster movie with characters who faced the camera and explained the plot, a forgettable product that generated millions. The people who sent those first postcards wanted something else.

Create for the crazy ones

It would be easy to view Eudora’s whipsaw growth and decline as a cautionary tale. In hindsight, Qualcomm almost certainly would have rather released Outlook than Eudora, would have preferred the software grow, and scale, and retain millions of users and billions of dollars.

But not from Dorner’s perspective. His clout permitted him to say no to Qualcomm’s request that he relocate to California, instead working from home at a time when remote work was unheard of. He was allowed to develop Eudora the way he wanted, for the users he had in mind. "To have other people use and enjoy your program is probably what a certain breed of programmer is really interested in. That's the ultimate reward,” he said in his interview with the New York Times.

As of 2024, people were still putting hours into modernizing Eudora for current hardware. All because the guy who created it wanted to make something more quirky than boring, more challenging than facile–something that prioritized a small group of fervent fans above the rest.

Header screenshot via old.accesscom.com/support/macintosh/mac-eudora2.html