You’d never expect to see a paper letter’s signature followed by “Printed on International Paper” or “Inscribed with a Montblanc” or “Delivered by the USPS.” An ad in the letterhead might almost be forgivable—“Ah, my friend was staying at the Waldorf Astoria and thought of me, how nice.” That, or a logo on the reverse of a card; we’re accustomed to those.

But an ad below the signature line would rank somewhere between a prank and a hostage note.

Yet that same seemingly sacred space became one of tech’s most valuable ad spaces, one that’d be recorded in US Congressional records and court cases for posterity.

It all started when investor Tim Draper wanted every Hotmail email to end with “PS: I love you.”

Spreading software like a virus

Hotmail as it started—via the Web Design Museum

The original webmail faced a dilemma: How to advertise a free product without breaking the bank?

The Hotmail team had landed $300,000 in initial investment and launched their free email service on July 4th, 1996. Slowly but surely, friends told friends. 100 people signed up the first hour, 50 or more the next, and the pace kept up. But slowly isn’t quite enough for venture-backed startups, and Draper wanted to throw fuel on the fire.

So, as the story was told in Adam Penberg's book Viral Loop, lead investor Tim Draper had an idea. What if every Hotmail email advertised Hotmail? What if, alongside your normal signature, every Hotmail email concluded with “PS: I love you. Get your free e-mail at Hotmail.”

Debate ensued. “I love you” was deemed a bit much. But the second sentence survived, complete with a link to Hotmail.

The sanctity of the signature line was shattered. Hotmail, meanwhile, took off like a rocket. “[Hotmail co-founder] Bhatia sent a message to a friend in India,” wrote Penberg, and within three weeks Hotmail registered 100,000 users there.” “It was as if Zeus sneezed over the planet,” wrote Steve Jurvetson about Hotmail in the paper that coined the term viral marketing.

18 months and 8.5 million signups later, Microsoft acquired the startup for $400 million, advertised by its own users. And the war for your signature line was on.

Putting your name to it

Classic Usenet signatures from a 1992 debate about Linux

Signatures and signet rings and seals date back to antiquity. They denote authenticity, trust. I wrote these words, and hereby certify so with my mark.

Little surprise that they made their way to the easiest computer communications. Usenet forums standardized signatures first, with a .signature file that’d automatically add your name and contact details to your posts. Signatures, typically, would be preceded by two hyphens and a space, then your signature on the following line—a style still commonly used to offset signatures in email applications today.

ASCII art showed up in signatures, alongside ads for products and services. You couldn’t simply excise them, though. “While signatures are arguably a blemish, they are a well-understood convention,” acquiesced RFC 1849: "Son of 1036", a 2010 followup to the original Usenet RFC from December 1987. What you could do is call for restraint. “Four 75-column lines of signature text is 300 characters,” advised the authors, “ample to convey name and mail-address information in all but the most bizarre situations.”

Yet everyone didn’t exercise constraint. “Signatures have become the graffiti of computers,” wrote Brendan P. Kehoe in his 1992 “A Beginner's Guide to the Internet”. That was only in reference to overly-long poems and ASCII art; ads were so rare as to be unimaginable. “Advertising in your signature will more often than not get you flamed until you take it out,” he cautioned. Little did he know that, at that time, the desecration had only just begun.

We didn’t start the fire

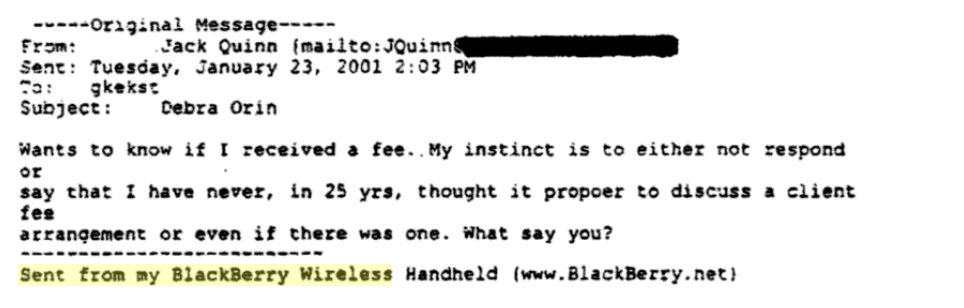

One of the earliest BlackBerry signatures on an email in 2001

For soon, branded email signature lines turned into a status symbol.

It started with the BlackBerry, the original smartphone, christened Crackberry by devotees and detractors alike. Early versions shipped with the classic “Sent from my BlackBerry Wireless Handheld (www.BlackBerry.net)” signature. It’s, perhaps, the email signature most documented in the historic record. It shows up in a January 2001 US Congressional report, in emails around Enron’s collapse that December, and in Karl Rove’s emails to President Bush in April, 2003 a month after the war in Iraq started.

By the 2007 financial crash, the signature itself had experienced rapid deflation, down to the trim “Sent from my BlackBerry Handheld,” recorded for posterity in the One Hundred Twelfth Congress’ “Wall Street and the Financial Crisis.”

Hotmail’s signature, at first, said you were an early adopter, but also that you were using a free email service. Not exactly a status enhancer. But the BlackBerry’s signature meant you were important, taking time out of your busy schedule to reply on the go, that perhaps you should be forgiven for typos and brevity.

“My boss persists in leaving his default BlackBerry signature at the bottom of his e-mails: ‘Sent from my BlackBerry Wireless Handheld (www.BlackBerry.net)’ — as if to say, ‘If I’m still working, why aren’t you?,” wrote InfoWorld's Steve Gillmore in December 2001. A subtle power play and status symbol wrapped in one.

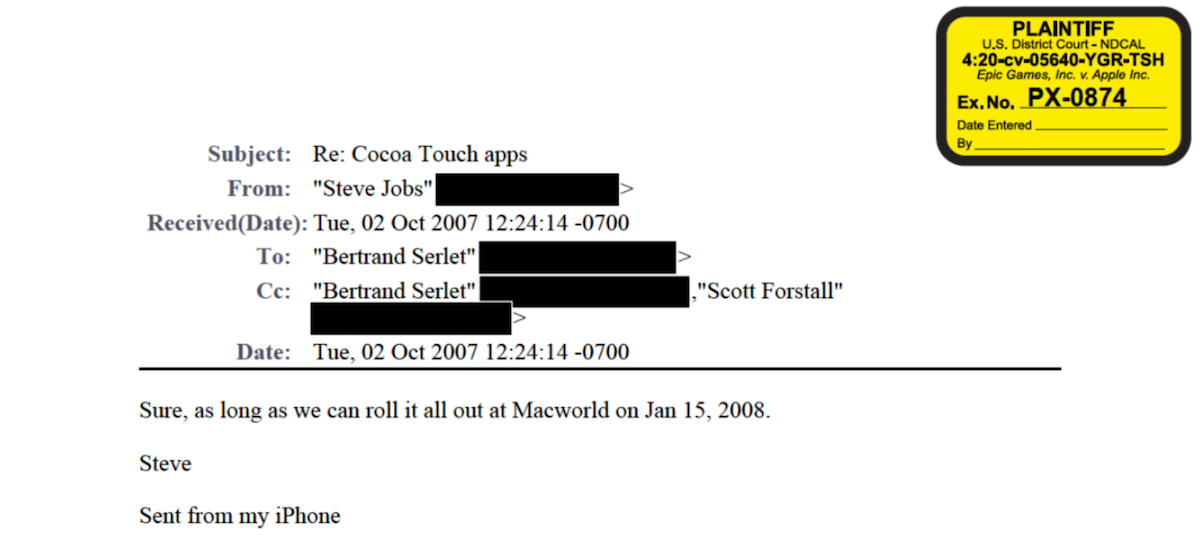

Steve Jobs' email signature, little over three months after the iPhone launched

Outside Wall Street and the Beltway, your emails may have not been important enough to require a BlackBerry. But when Steve Jobs pulled the iPhone out of his pocket in 2007, suddenly a smartphone was the coolest device you could own. It, too, came bundled with the now-ubiquitous “Sent from my iPhone” email signature, it too a humble-brag at owning the newest device and apology for typos in one. Even Steve Jobs left his default signature on, preserved for posterity in Epic Games, Inc. v. Apple Inc. court case discovery documents.

The signatures with the most staying power say something about the sender—for better or worse. The reportedly $24,000/year Bloomberg trading software appends “Sent from Bloomberg Professional for iPhone” to emails, a signature that started out as “Sent From Bloomberg Mobile MSG” in 2006. Superhuman, the $30-a-month email service launched in 2007, does the same, with “Sent via Superhuman” included below your email signature. And, reportedly, that signature “drove 50-60% of website traffic and is still one of the main engines of growth” for Superhuman. It’s not like you can carry your Bloomberg terminal or Superhuman subscription on your arm like a luxury watch or bag. The signature’s both an ad and a hint to recipients about your place in the pecking order.

That, or the fact that you don’t care about changing your defaults. “People generally only change stuff that interests them or bugs them, and for most people this occupies neither category,” said @protomyth on Hacker News. After all, carrier-specific signatures like “Sent via the Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra 5G, an AT&T 5G smartphone” feel less likely to inspire envy, yet they too live on, clogging up the conclusions of emails all the same. They round to little more than email forensics, announcing every detail of your device and cell service choices with each message you send.

Signatures as a reflection of the internet

Somehow, email signatures turned out to be a microcosm of the internet. They were raw, indie, internet graffiti in the spirit of punk rock and zines. They were messy, unexpected, yet beautiful in their own way, a tiny example of the internet up and through Geocities.

Then came commercialization and the dot com bubble, with free software sponsored by ads, built on the hopes of ever-increasing valuations and user bases. And with that came ads in email footers, first to drive product adoption, then to signal that you were part of the cool (or busy) crowd.

Today, odds are you don’t give all that much thought to your email signature. Even if your device or email app adds a signature, we’ve become inoculated to the ads and scan with scarcely a second thought. And with AI now auto-summarizing emails into notifications, we’re less likely than ever to see whatever bits of data get appended to messages.

In hindsight, at least loud obnoxious signatures were human. They were unique and premeditated and crazy, yes, but someone’s craziness. Someone took the time to string those words and characters together. That means something. That’s the thing we want to see more of on the internet.