One of the earliest attempts to tackle spam online sent so many automated notifications to list subscribers in a short timeframe that it crashed an email server. It was 1993 and Dick Depew had created a program to flag and “cancel” certain types of Usenet messages. What could go wrong?

Dick had forgotten to exempt cancellation announcements from his moderation filter, creating a recursive loop where those very messages generated new cancellations, which generated more, and so forth. The event “inspired widespread resentment among those who pay for each message they have downloaded.” He was pilloried and, for the first time in Usenet history, shamed for spamming.

Ten years and ten days after Depew’s Frankenstein program terrorized news.admin.policy, CAN-SPAM was introduced on the Senate floor to provide a legal framework for dealing with “extremely rapid growth in the volume of unsolicited commercial electronic mail.” Don’t let the 1-star rating on Goodreads fool you–it’s riveting stuff. More than 10,000 words of legalese to inspire fear, anxiety, and confusion about how to send your newsletter without getting into trouble!

I’m kidding. Many of CAN-SPAM’s requirements are handled by newsletter platforms on the backend. And, for what it’s worth, most newsletters aren’t subject to its rules in the first place (but I’m no lawyer!). What newsletters are subject to, however, is a hit to deliverability when subscribers mark an email as spam, an avenue for retribution that has absolutely nothing to do with CAN-SPAM. So, take care of the very few things it asks of you and work your way up from there.

Stuff you don’t need to worry about

While the word “unsubscribe” never appears in the 2003 draft of CAN-SPAM, it’s arguably the most impactful part of the law. Recipients expect (nay, deserve) a way to opt out of future emails. Anyone who wants out but can’t find the link will hit that Report Spam button faster than Dick’s Automated Retroactive Minimal Moderation script flooded Usenet.

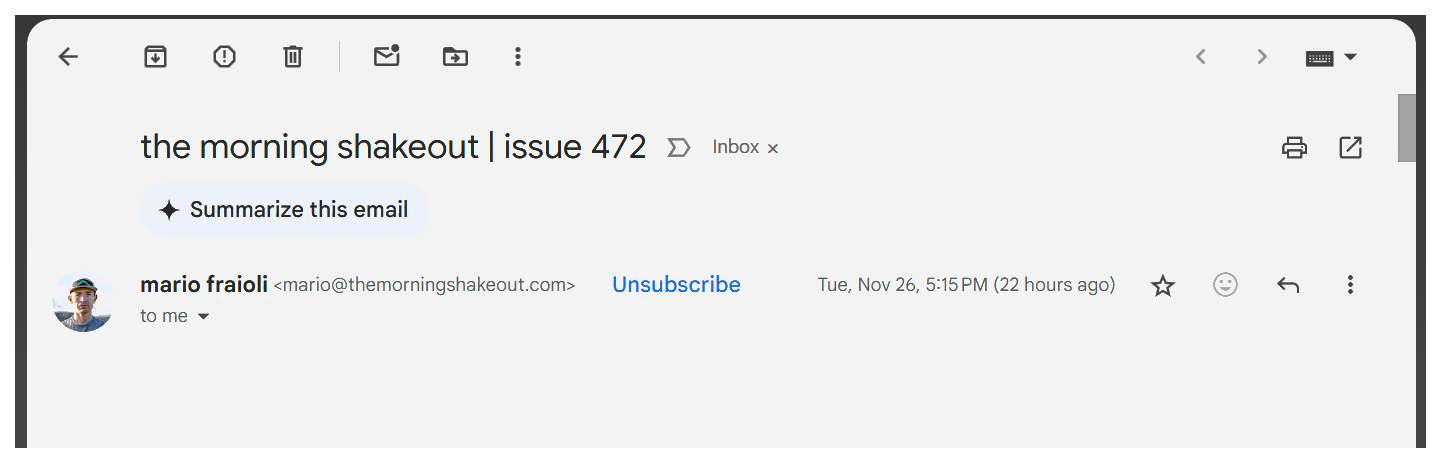

After more than 21 years on the books, the internet collectively agrees that one-click unsubscribe is the best opt-out option. It’s the tag in email headers that lets clients like Gmail show an unsubscribe button, typically next to the From field, in email newsletters. Absent that, there should be unsubscribe links at the bottom of all your emails. At this point, though, you’d almost have to go out of your way to find a platform that doesn’t include both options and makes them impossible to disable. One less thing to worry about–huzzah!

What are left up to you to monitor, however, are direct replies to your newsletter. You should respond to them as quickly as possible since it shows subscribers and email processors that you are a sender acting in good faith. And, for CAN-SPAM compliance, you must remove anyone from your list within 10 business days if they send a plain language request to be unsubscribed.

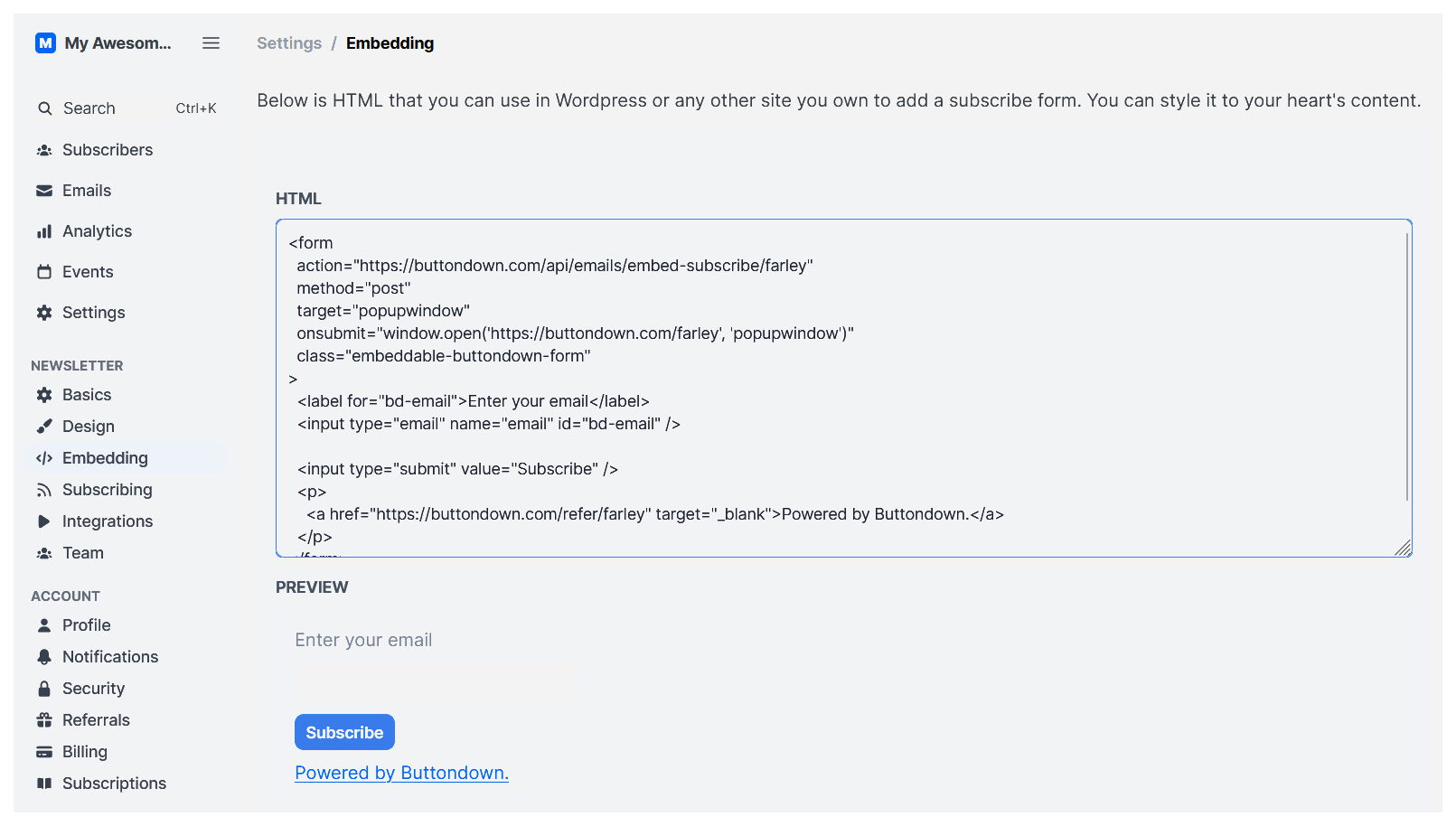

Similarly, your newsletter platform can steer you toward CAN-SPAM's physical address requirement by making it a prerequisite for account approval. If your newsletter is primarily commercial or promotional, every one of your emails must include a physical address. But, it does not have to be your home address! It can be a PO box, or a private mailbox. (If you’re a Buttondown user you can use our address: 304 S. Jones Blvd #3567, Las Vegas NV 89107.)

Finally, there are a handful of technical things that happen in the background to prevent you from providing what CAN-SPAM calls “header information that is materially false or materially misleading.” But the tl;dr is that, for the most part, everything at the very top and bottom of the email is likely railroaded by your newsletter platform to forestall noncompliance with CAN-SPAM.

Everything in between is up to you.

How to avoid being labeled a spammer

Even though the remaining requisites aren’t exactly black-and-white, adhering to them is as easy as whipping up a spam, egg, spam, spam, bacon, and spam breakfast. First, don’t add people to your list who didn’t ask to be added. Second, don’t send anything deceptive, manipulative, or misrepresentative. That’s all!

In 2003, when the CAN-SPAM bill was drafted, the phrase to describe spammy list growth was “address harvesting.” That includes web scraping, so-called “dictionary attacks” (randomly guessing thousands of email addresses to send to), and buying lists. Double opt-in acts as a fantastic failsafe here but isn’t applicable 100% of the time, such as when someone confirms their subscription via checkout process on another platform like Shopify. If a subscriber doesn’t sign themselves up via a form you created (e.g. on your website, eCommerce page, or newsletter archives), they shouldn’t be on your list.

For the people that you do end up sending to, CAN-SPAM is particularly concerned with the name your newsletter shows in the From: field and the contents of the subject line. You cannot, for example, list your name as Keanu Reeves (there’s only one!) and promise a puppy cafe date (who could resist!?). The honesty clause also applies to the body of your email, though, and one of the first criminal cases tied to CAN-SPAM involved emails advertising “bogus diet patches.”

Speaking of advertising, it’s worth reiterating that consumer expectations of CAN-SPAM’s requirements are generally much higher than what’s actually included in the law. For instance, most of your subscribers probably want you to call out when you’re being paid by a third party to include something in your newsletter. That doesn’t seem to be required based on the current wording. But you should do it anyway (and it may be required by the FTC)!

Avoiding Uncle Spam is an excellent baseline

All that’s required of you to stay on the right side of America’s foremost anti-spam rules is to pick a reputable newsletter platform, respond to unsubscribe requests, include a physical address in your emails, only add people who want to be added, and be honest. But as Dick Depew learned the hard way, the legal and cultural definitions of spam can have less overlap than you’d expect.

Thankfully, going “above and beyond” doesn’t actually require going all that far. As long as you aren’t too pushy with your sales pitches, overdoing it with affiliate or suspicious links, inserting broken links and images, or sending emails more often than people want, you’ll be just fine. If you have the technical chops, you can dig into the weeds a bit with Postmark's spam score checker and Google’s Postmaster Tools.

Then, when you have the time, you might start thinking about how to avoid the annoying-but-not-as-maligned Promotions tab in Gmail. All that really matters, though, is creating fun and interesting content for people who took the initiative to sign up for your work.

Do that and no one should mark your messages as spam.